The one thing we know about COVID-19 so far is that there are many more questions than answers. Healthcare payers in the United States, including health insurance companies, risk-bearing healthcare providers, self-funded employers, and others are in a time of great uncertainty. As with everyone around the world, payers are braced for bad news. In the past several weeks, Milliman has developed macroeconomic and microeconomic models so that we can answer our clients’ questions. Developing useful models in an environment with ever evolving data presents unique challenges and has highlighted the difficulty in understanding how COVID-19 may affect healthcare costs. Based on this experience, we have identified some of the cost drivers that payers may expect to encounter both now and down the road after we get through the initial surge of the pandemic. At this point, it's a process of sorting out the knowns from the unknowns, and the unknowns still dominate.

Here is a quick checklist of issues for payers to keep in mind in terms of areas of focus as we move forward.

Infection rate and testing: How many people get this?

The most critical question right now is the actual infection rate and how to determine it. The variation in the availability of testing in different places worldwide has made this more difficult than anticipated in most pandemic action plans. In many situations, people believe that they are infected but cannot have their beliefs confirmed; it is also believed that some infected individuals show no symptoms but can pass the infection to others. Without a clear set of confirmed cases, it is hard for a payer to estimate the severity of infections or the need for medical services within their population – with a suspect denominator, all sorts of other questions become more difficult to answer. Without a clear view on the percentage of the population affected, estimates of the number of eventual infections could be off by an order of magnitude.

Deaths or hospitalizations may be the more reliable metrics, but the number of people who have COVID-19 is highly uncertain. Attributing deaths or hospitalizations to COVID-19 requires testing because the diagnosis cannot be made on clinical grounds alone. While we expect most seriously ill patients with COVID-19-like symptoms will be tested, any gaps in testing will result in unrecognized COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths.

This highlights the important issue of consistency (or lack thereof) in measurement of cases. Because the symptoms of COVID-19 are so similar to flu and pneumonia, a reliable determination of cases of any severity requires testing. To make matters even more complicated, the recommendations about who should be tested have changed significantly over the last couple of months and are expected to continue to change over the upcoming months in relation to the disease burden in different communities and the availability of tests.

Hospital capacity and services

In this pandemic, patients and healthcare providers are often confronted with a lack of hospital beds and medical support equipment. On a certain blunt level, for payers a patient who cannot get a hospital bed might represent a lower cost—if there's nothing to reimburse—but they may also represent a higher cost if the patient is treated in an out-of-network or non-traditional setting, or defers care until it requires more complex and costly interventions. If the government responds and provides additional staff support or sets up military-style field hospitals, payers could ultimately be responsible for paying a portion of those costs, which could be more or less than typical contracted rates. On the other hand, if a private hospital expands its facilities to include extra bed capacity, payers would then likely be billed at the hospitals’ and physicians’ usual contracted rates. “Outlier” provisions for extraordinary lengths of stay in those contracts will be very important. Some payments could be subject to retroactive settlements.

Also, a lot of necessary improvising is going on in this crisis, such as refitting ventilators to be used by two (or more) patients at once. It is not yet clear how these types of innovations will translate into costs for payers.

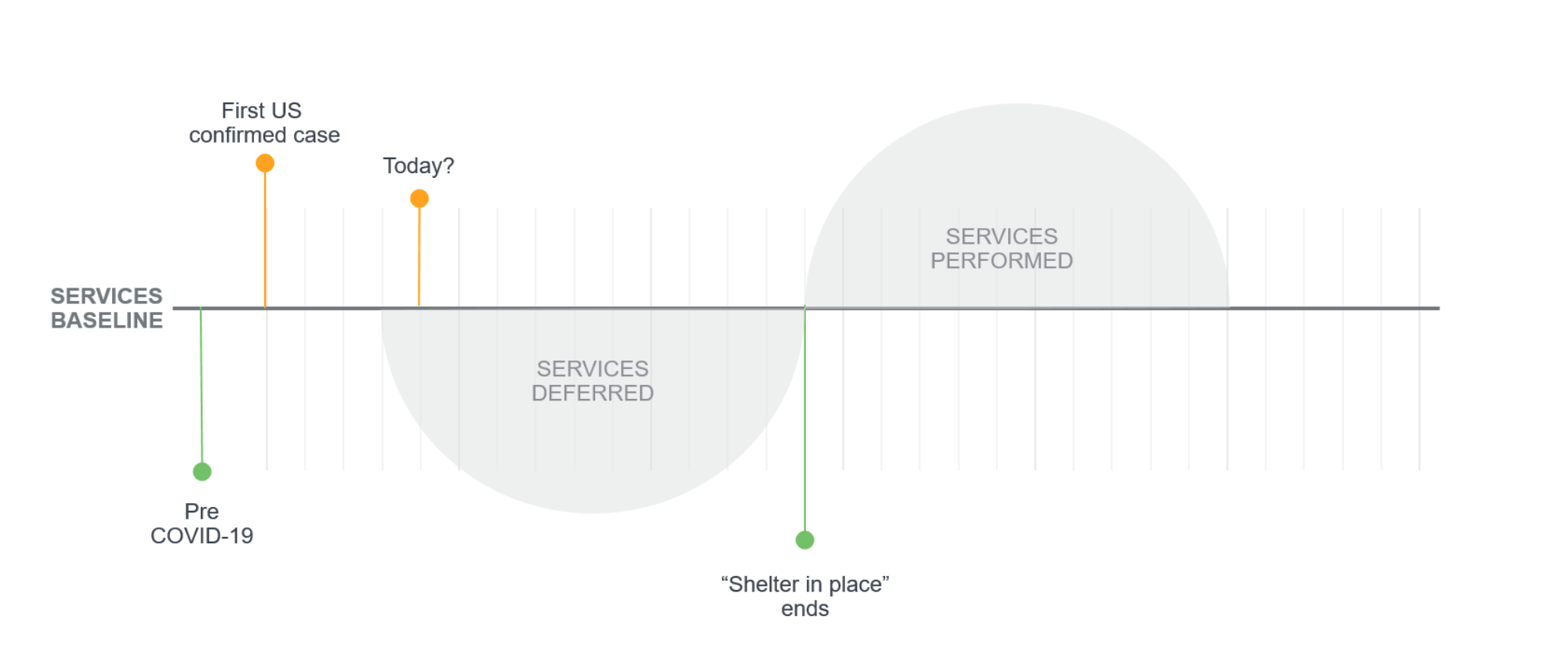

Figure 1 illustrates one potential scenario. Medical services are now being deferred, leading to pent up demand, which may be released after “shelter in place” orders are rescinded.

Long-term effects

People who suffer from COVID-19 and recover might face long-term health issues well after they recover. For those who do not suffer from COVID-19, long-term adverse health status from undertreated chronic care and delayed preventive care generally provided in face-to-face visits may become significant, although telehealth expansion is already filling some gaps that might otherwise occur. Elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures, and ongoing care that can only be provided through face-to-face care are being postponed to address the pandemic, which could represent a period of lower costs for insurers, but have the potential to show serious second order effects as the crisis continues. How long can face-to-face care be deferred, and what will manifest when all is said and done?

Some people are not receiving in-person visits to clinics and doctors at this time due to federal, state, or local instructions to providers on services that can be offered, while others are voluntarily staying away based on fear or prudence. Some of these visits may be being provided via telehealth, and others may not be occurring at all. Although some healthcare services may be deferred indefinitely, avoidance of others could eventually result in worsening medical conditions, especially if telehealth is not filling the gaps. At some point in the future, there could be a surge of pent up demand from patients for needed care as the pandemic wanes. This surge could be even more costly than any current savings if untreated conditions have worsened by that time. Figure 1 illustrates the concept of a surge that matches the magnitude of services deferred, but at this point, we don’t know how the “services deferred” and ”services performed” will measure up. Additionally, the current pandemic crisis is causing significant emotional stress to many individuals, which may manifest in increased behavioral health needs down the road.

Related to the state of the economy, how will the current downturn affect future health risk pools as individuals who lose their jobs enter either the Affordable Care Act (ACA) individual market, the Medicaid market, or become uninsured altogether? For those who may join the ACA risk pools through a Special Enrollment Period, which members will stay in the risk pool once the pandemic is over?

Last but not least, what adjustments will need to be made to 2020 and 2021 experience data in order to use it for future cost projections?

Telehealth

Telehealth may be about to have its moment in the sun and explode as a more widespread practice in the same way that working from home may change our society significantly, too, potentially including post-pandemic effects. At the moment, telehealth has turned into a useful and necessary way to protect physicians on the front lines of COVID-19, provide needed medical care to patients who do not require an in-person encounter, and triage patient complaints to identify those who require face-to-face care in order to minimize patient exposure to COVID-19 in the healthcare environment. The pandemic has forced this rapid expansion of telehealth, but it also seems at least likely that telehealth will be more "normalized" and widely used in the future. Beyond the myriad clinical and operational challenges associated with telehealth, its use raises technical issues for payers and regulators, such as deciding whether diagnoses recorded via telehealth should be included in risk adjustment calculations. Issues surrounding the disparity of reimbursement for telehealth and face-to-face visits will also almost certainly need to be addressed.

Other known unknowns

It is possible that resources will be strained even further as healthcare workers contract COVID-19 themselves or, in some cases, simply burn out and walk away from the extraordinary sacrifice society is asking of them. It is difficult to know how to anticipate or calculate these costs for insurers. To the extent that the supply side suffers, what will happen in terms of both healthcare costs and effectiveness of outcomes?

Differential mortality in specific populations may become a significant factor for post-pandemic costs. If the pandemic heads in the most severe direction feared and very large numbers of people die, the cohort with the highest COVID-19 mortality may contain disproportionate numbers of high-morbidity, high-cost patients. This could alter the risk profiles of populations in material ways.

We do not know exactly what effective treatment of COVID-19 will involve in the future because optimal care is still being studied in clinical trials. Some of the potential treatments being investigated now are relatively cheap, while others are expected to be very expensive. Moreover, identification of the role of potential treatments at various points in the course of COVID-19 disease is a work in progress. Another unknown but potentially costly factor is the health of survivors, who could have lasting health effects from the infection that require significant healthcare services.

In risk-adjusted markets, these calculations are another area of concern for carriers going forward – how will COVID-19 claims affect those calculations, and how will that differ across markets such as the ACA markets, managed Medicaid programs, and Medicare Advantage (MA) and Part D? Large movements of individuals across these programs and differences in the structure of the risk adjustment mechanisms will further complicate the already complicated risk calculations for both regulators and payers. Timing issues will also create potential problems—for example, will disruptions to care in 2020 lower the prospective risk scores used to pay MA plans in 2021 just as there is a surge in deferred claims? How will Star ratings be affected?

Carriers are operating independently in terms of how to estimate COVID-19’s impact on future claims (and premiums) – naturally, a range of opinions will result. How will this dynamic affect future markets (including the silver plan benchmark in the ACA)?

Unknown unknowns

Much depends on what is still to happen. How long does the pandemic last? How flat will the curve eventually get? Where does it peak, and how much wider does it become as it flattens? How does it spread through the country? How dramatically is your region affected? New York costs will likely look very different from Alabama costs, for example. How quickly is effective treatment found? What is the risk composition of your population, and how will it change? Older populations appear to be at greatest risk. Will risk adjustment assumptions and calculations need to change, including calibration of models built on 2020 data? Who will pay for testing, especially if it needs to be conducted on a mass scale? Will we see lasting mental health effects in terms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related syndromes? In terms of the economic impact, how will Medicaid expansion and ACA-subsidized populations be affected? Will we see lasting and permanent changes in the way care is delivered and where people get their health insurance coverage?

Perhaps most important of all, what haven't we thought of yet?